This Friday Marabou is thinking about the power of objects. As Indigenous Peoples’ Day approaches in the United States, the discussion of whether or not statues of Christopher Columbus should be taken down is back in the mainstream. We as humans imbue objects with power. Mere pieces of fabric sewn together transform from textile to flag, representing a country’s history, morals, and values. Bronze or marble shaped in the likeness of a person transform into sculptures that inspire or oppress. In 2017, the potential removal of a Robert E. Lee statue in Charlottesville, Virginia resulted in mobs of men with tiki torches descending upon the city to “defend” the statue. Heather Hayer, a woman protesting for the removal of the statue, lost her life when a man ragefully drove his vehicle into the crowd of protestors. Seeing the visceral, emotional reactions and national public debate that surrounded the removal of a piece of metal makes it hard to stay, “It’s just a statue.” We as humans have been creating objects injected with our beliefs and values since we’ve been able to think complexly. The British Museum’s “I Object” exhibition of curated objects of dissent pulls a bronze sculpture of Augustus Caesar, first Emperor of Rome, from its usual home in the Roman galleries and uses it show how a mere sculpture can embody, confront, and challenge power.

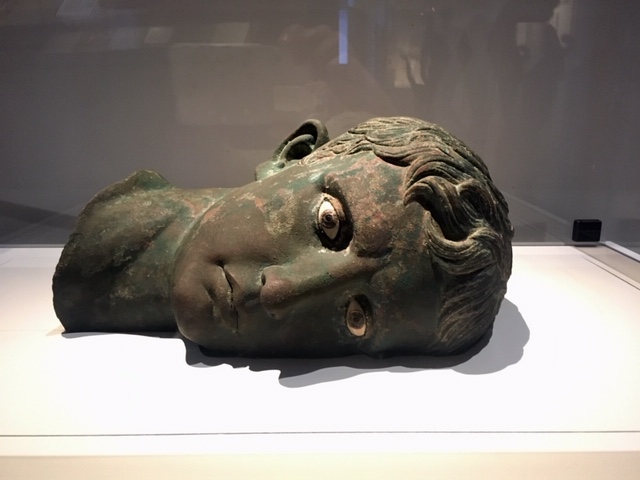

After becoming Rome’s first emperor, Augustus Caesar (née Octavian) created an entire sculptural propaganda program intended to make his presence felt across the vast empire all along the Mediterranean coast of present-day Southern Europe and North Africa that stretched from present-day Spain to the west and present-day Syria to the east. Augustus commissioned idealized statues that would display his military prowess, abilities as an orator, and portray him as youthful and invincible. The statues would be standardized and placed throughout the empire. The images would be full-body depictions of the emperor, which is what made the 1911 unearthing of just Augustus’s head so compelling.

The head of Augustus was found under the steps of a temple dedicated to victory in Meroë , an area geographically outside the domain of Roman rule, located in the Nubian Kingdom of Kush just south of Egypt in present-day Sudan. (Side-note: the 25th Dynasty of Egypt was Nubian from c. 712-664 BCE, speaking to the power and influence of Egypt’s Nubian neighbors to the south). The excavators did not know in 1911 that they had found an object that tells an incredible story of power play between the Nubians of Meroë and the Romans. As Rome expanded into Egypt and moved southward, the Merotic army was ready to push back. It is believe that the bronze head of Augustus was acquired when the Merotic military captured a series of Roman forts and towns in southern Egypt. The forces were managed by Candace Amanirenas (Candace is the Merotic word for queen) and in their raid they beheaded the statue of Augustus literally and symbolically removing the head of state, if you will. Augustus’s bronze head was then brought back to Meroë and buried underneath the steps of the temple of victory to add insult to injury as the people of Meroë trampled the Roman emperor’s head and (symbolically) his empire as they entered and exited the temple.

Marabout shares the story of the head of Augustus found in Meroë because it speaks to what we are dealing with today in navigating how to deal with public imagery that is inspiring for some and oppressive for others. The head of Augustus dates to 27-25 BCE. Almost 2,000 years later we still react to statues as having more value than just their inherent materials. The sculptures of Augustus were intended to exercise and enforce power, but the Nubians turned this use on its head (Marabou couldn’t help the pun) and used the statue and likeness of Augustus in an act of subversion. Marabou believes public statues representing oppressive values and ideas should be removed, but if they won’t be taken down, what are the creative ways people can transform the power of these objects to work in their favor? Marabou leaves you with that question and the following two to ponder as you make your way into the weekend:

When was the last time an object stirred strong feelings in you?

What objects do you value as representations of your beliefs, values, and morality?